Envisioning

Our Coast

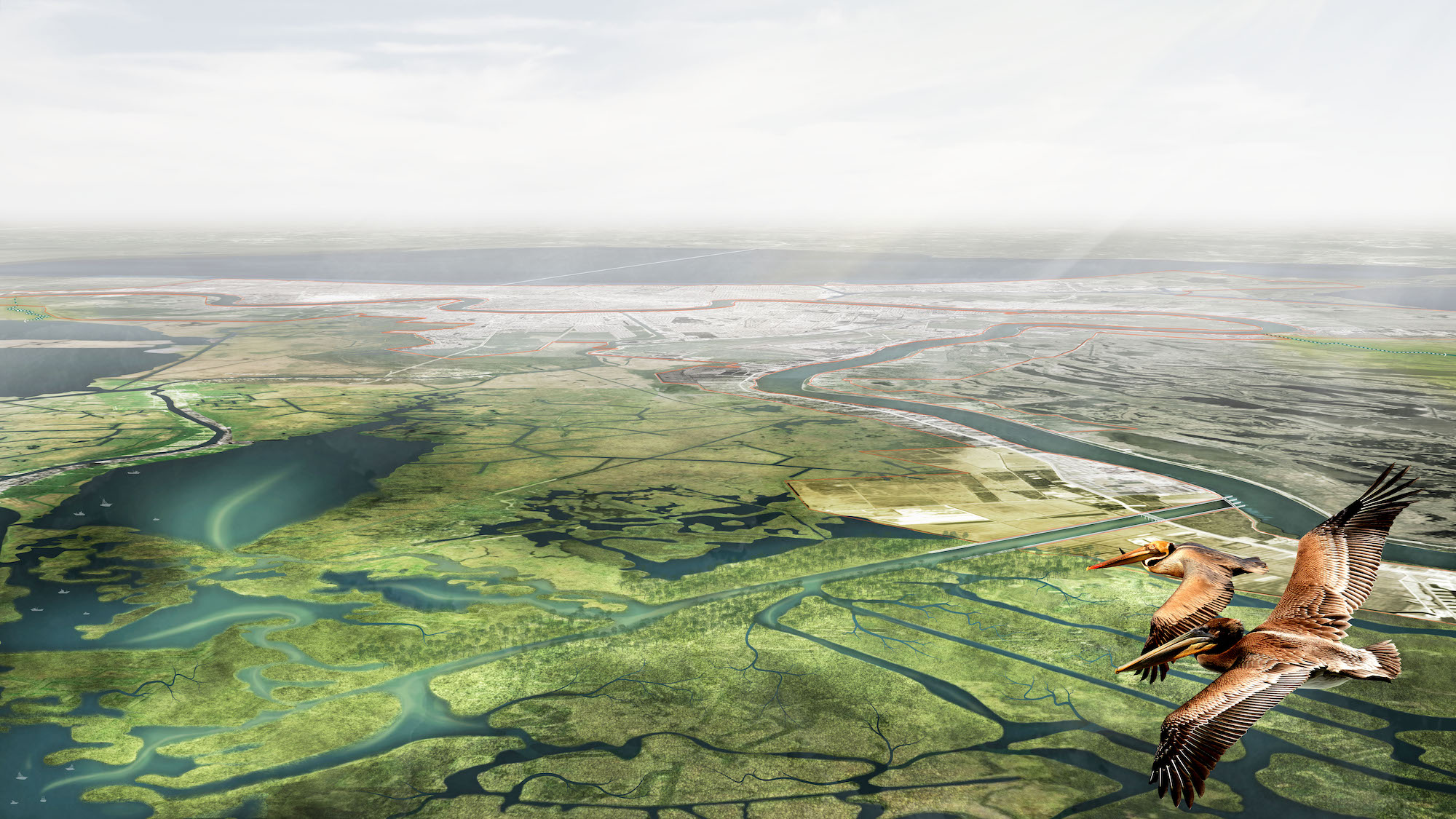

The fate of our Louisiana coast is in our hands. A revived coast is within reach. Though the wetland footprint will be smaller, reconnecting the Mississippi River to our coastal wetlands means it could be far richer than anything we’ve seen in our lifetimes. To get there we must act to carry out Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan, the plan of today, and the projects that our collective vision add to future versions.

What does the envisioned Future Coast

Look Like?

Our Future Coast looks a lot like what Old World people found when they arrived here 300 years ago and first met indigenous communities; A coast teeming with bountiful wildlife, birds, fish and shellfish — an abundance that has been lost for generations. We lost that abundance when the Mississippi River lost its connection to our coastal wetlands — but we can get it back with well designed restoration projects that harness the power of the River to build new land the way nature always intended.

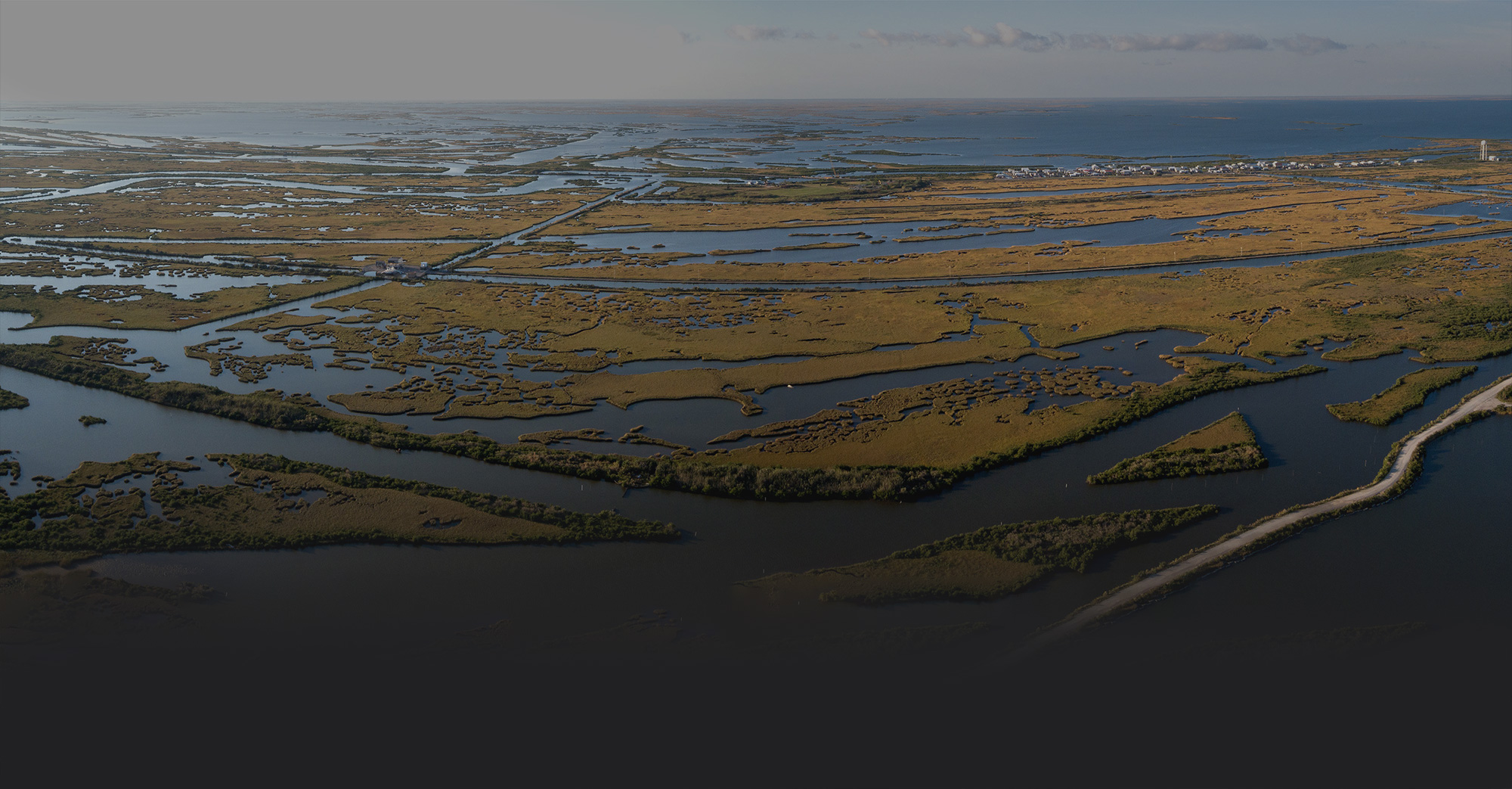

The most rapidly disappearing land in America

Because of human attempts to control the river and modify coastal wetlands, what had been growing is now shrinking. Wetlands laced with bayous, bays and battures are sinking at the fastest rate in our country, and now the sea is rising at an ever-increasing pace. The clock is ticking to be sure, but it has not yet run out.

The Future Coast

Is Possible

Louisiana is home to America’s youngest land, building in the few areas where the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers are allowed to run free. Forces that we can’t control guarantee that much of our coast will disappear in coming decades. But we have a window of opportunity right now to get ahead of sea level rise. We can grow new land that can keep up with rising seas by reconnecting the River to our coastal wetlands.

Envisioning

The Opportunities

Ecological

Restoring the coast is about more than just saving wetlands, it’s about restoring the natural balance between land and sea that healthy deltas provide. Before we interfered, the Mississippi River was able to build new land in one area of the delta while the sea reclaimed older delta land nearby. Nature was in balance, and the result was an abundance of life: wintering ducks and geese in freshwater areas, extensive oyster reefs where the fresh and the saltwater met and vast colonies of iconic Louisiana animals like the brown pelican in the salty bays.

Economic

Louisiana’s coastal economy relies upon three things:

- Location: Where the greatest inland waterway system in the world — the Mississippi and its tributaries — meets the world’s oceans and shipping lanes. A gigantic network of ports connect inland North America to the rest of the world on the Louisiana coast;

- Natural Resources: whether seafood in its estuaries, ducks in its marshes or oil and gas buried deep beneath its soils, the delta is incomparably rich; and

- Tourism: people from all over the world come to experience its resources and the vibrant culture that depends upon them.

The envisioned Future Coast will rely upon the same foundations, but will be different, changed by emerging circumstances:

- Louisiana’s ports rely upon nineteenth century techniques to keep navigation channels open. The future must bring a navigation system that allows the ships to reach our ports, but retains and distributes freshwater and sediment from the continent to build and sustain wetlands.

- Though a major supplier of wild caught seafood to the nation, competition from overseas aquaculture threatens the livelihoods for Louisiana harvesters. If integrated into the fabric of restoration, innovation can keep Louisiana competitive and provide a bridge to an abundant future for traditional harvesters.

- A coast reconnected to its River will provide opportunities for continuing to catch, hunt and enjoy the fish and wildlife we know today, though not in the same locations. Charged by the River’s energy, the future coast will allow expansion of ecotourism, hunting and fishing, and will support greater abundance and variety.

Economic Opportunity

Restoration at the scale needed is costly, but spending the money now saves money over the long run and creates new jobs and economic opportunities. This comes just as the world begins the transition from the old fossil fuel based economy to one based on renewable energy and sustainable systems.

- As the most rapidly sinking place in the United States, Louisiana’s innovations can be exported to coastal areas around the world as they face what we have already learned to overcome: rising seas.

- Other industries will also see the positive effects, with new emphasis put on transitioning to renewable energies like wind and solar power, and even the electrification of maritime transportation and machinery.

How do we

get there?

Sediment Diversions

Implement controlled diversions of river water to carry sediment that revives collapsing wetlands by capturing river born soils, and build new land where the old has disappeared.

Barrier Islands and Headlands

Manage barrier islands and headlands not as fixed places, but as part of an evolving and responsive delta system that creates natural balance.

New Navigation Options

Find a means to allow ships to navigate into and out of the ports without allowing saltwater to intrude and freshwater and soil to escape.

Natural Barriers

Buffer communities from hurricane surge and rising seas by rebuilding natural barriers.

Healthy Estuaries

Maintain healthy estuaries by restoring the natural balance between fresh and saltwater.

Limit Wetland Loss

Prevent or reduce erosion of wetland shorelines caused by human activities, relying wherever possible on natural solutions like oyster reefs.

Where Do

We Focus?

Given the variation across Louisiana’s coastal basins, including differences in geology, biological diversity and human habitation and use, taking a basin-by-basin approach proved to be most effective. Assessing each basin’s impact and sustainability separately allows for the integration of multiple restoration measures within the context of a specific portion of the coastal landscape.

Coastal Basins

A basin is an area that is hydrologically connected, such as a river basin, lake basin or drainage basin. Assessing each basin’s impact and sustainability separately allows for the integration of multiple restoration measures within the context of a specific portion of the coast.

Barataria Basin

The Barataria Basin has played an essential role in the production of natural resources and shaping the rich history and development of Southeastern Louisiana and New Orleans. This basin's estuary serves as a bountiful host to some of Louisiana's oysters, shrimp and fish, feeding locals, visitors and the nation. Protecting this area is critical, and it starts with implementing sediment diversions and managing sediment retention. Projects are already underway in the Barataria Basin, including storm surge management systems, maintenance of barrier island system and efforts to rebuild marsh. Together, these projects will propel Barataria towards greater prductivity.

View Barataria Basin ProjectsFacts and figures

According to the Louisiana CPRA, there are 89 active projects in the Barataria Basin, benefitting around 1.37 million acres.

Between 1932-2016, the Barataria Basin lost 430 square miles of land.

Between 1974-1990, the Barataria Basin lost an average of nearly 5,700 acres of wetlands per year.

Pontchartrain Basin

Pontchartrain Basin is the most populous and expansive coastal basin in Louisiana, playing host to 40% of Louisiana's 4.66 million people, making it the most densely populated basin in the region. The projects targeting Pontchartrain are chiefly concerned with managing storm surge, strategically rebuilding land bridges that separate major water bodies and getting the balance of fresh and saltwater right.

Facts and figures

According to the Louisiana CPRA, there are 48 active projects in the Pontchartrain Basin, benefitting around 1.36 million acres.

Birdsfoot Delta

As home to the navigation channel for seagoing vessels making their way into the Mississippi River, the iconic delta is significant not only to the state but also to our nation's economy. This region is a critical habitat for a large number of wading birds, as well as more than one million waterfowl annually, making it deeply intertwined with our local ecosystem. The effects the outdated navigation system on the Birdsfoot Delta have strained, with soil wasted by dredging and jetties sending it into the deep Gulf. Projects in the delta focus on designing a navigation system that can accommodate natural distribution of water and sediment.

Facts and figures

Between 1932-2016, the land surrounding the Birdsfoot Delta has diminished from 262 square miles to 117 square miles.

The Birdsfoot Delta is where the mighty Mississippi ends its journey of more than 2,000 miles to meet the Gulf of Mexico.

Tens of thousands of wintering waterfowl, wading birds, secretive marsh birds and shorebirds utilize the Birdsfoot Delta’s rich food resources.

Terrebonne Basin

Initially named for its "good earth" by early settlers, this basin provided highly fertile soils and a freshwater source to inhabitants before its wetlands were devastated in the 20th century. To this day, the “terrebonne” reputation holds true, but it is under attack. Dubbed "restore or retreat country," this area defines the bayou and its uncommon culture. Suggested projects revolve around rebuilding and maintaining barrier islands, reintroducing freshwater from the Atchafalaya River and rebuilding the sunken natural ridges that once protected interior communities.

Facts and figures

According to the Louisiana CPRA, there are 48 active projects in the Terrebonne Basin, benefitting around 28,600 acres.

The Terrebonne Basin lost 500 square miles of land between 1932 -2016.

Greater Atchafalaya Basin

The once extensive reefs along this basin had reduced the exposure of shorelines to erosive waves, moderated tidal exchange and storm surges, and retained freshwater and sediments within the coastal zone. Currently, the Greater Atchafalaya Basin is the only region along the Louisiana coast that did not experience land loss, with positive gains exceeding 1.5% per year since 1998. Maintaining this growth through sediment diversions while monitoring water salinity to ensure ecological stability will be the focal points within this area.

Facts and figures

There are 65 species of reptiles and amphibians that live in the Atchafalaya Basin.

The Greater Atchafalaya Basin has an estimated average annual commercial harvest of nearly 22 million pounds of crawfish.

The Atchafalaya Basin has gained six square miles between 1932 - 2016 and is the only basin in Louisiana to experience net land gain.

The Greater Atchafalaya Basin is home to 1.4 million acres of bottomland hardwood and bald cypress-water tupelo swamp.

Chenier Plain

Particularly valuable for its abundance, diversity of life and natural resources, the Chenier Plain also provides vital stopover for migrating songbirds and shorebirds. National and state refuges, along with private lands managed for natural resources, bolster the local economy with hunting, fishing and wildlife observation opportunities. Restoration efforts are focused on limiting saltwater intrusion and managing freshwater distribution to maintain marshland, with additional benefits to adjacent agricultural land.

Facts and figures

The Chenier Plain is the wintering home of more than 5.8 million ducks.

More than 360 species of birds can be found in the Chenier Plain including ducks, geese, herons, egrets, ibis, storks, spoonbills, raptors, shorebirds and neotropical migrant songbirds.

Let’s Make The

Future Bright

The state of Louisiana’s coast has put us under the nation’s spotlight. What we do with this attention is now up to us. It’s time to show the world a new Louisiana. One that is innovative and sustainable — one that will be a catalyst for change. Together we can pave the way for coasts around the world and set a new global standard.